This is a question which has been doing the rounds on social media for as long as I can remember, do cycling cleats make you faster? It’s a surprisingly complex topic, and worthy of a bit more explanation than a couple of paragraphs on a combative thread. First things first, there are two things cleats do not do.

This is a question which has been doing the rounds on social media for as long as I can remember, do cycling cleats make you faster? It’s a surprisingly complex topic, and worthy of a bit more explanation than a couple of paragraphs on a combative thread. First things first, there are two things cleats do not do.

They do not give you more power, and they will not give you free speed. They can make you faster if used correctly, but it’s not as simple as declaring that they give you more power. Power is a product of torque (how hard you push down through the pedal) and speed (cadence). Unless something generates more torque for us (such as a motor), or increases the rate at which we’re pedalling, it cannot generate more power. Cycling cleats will probably make you faster though, for a few reasons.

This is the one that people like to quote, better power transfer through the pedals. This comes primarily from two areas, the cycling shoe you use, and the ability to change your pedalling mechanics.

By wearing a cycling shoe with a stiffer sole, you avoid losing any power to the flex in the sole of a trainer. All of the power goes through the cleat itself, straight into the pedal, then the drivetrain, generating power. However, it probably won’t improve your efficiency by anything close to the 20% like some will try to claim. However, it does give us the potential to generate more power, at a cost.

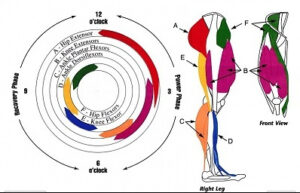

To understand this a bit closer, let’s look at the muscles used in the pedal stroke.

Being clipped in allows us to recruit muscles in the upstroke which we cannot easily engage with flat pedals. These are generally muscles used between the 6 O’clock and 12 O’clock position. If we look at these muscles which are otherwise unengaged, it’s primarily the ankle flexors in your shin, hamstrings and hip flexors. Now the hamstrings are a big muscle group, but the others? Not so much.

Even though our hamstrings are working, how many times have you climbed off of your bike nursing sore hamstrings? I can’t say I ever have, nor have I heard anyone complain of that. So despite the fact it’s a big muscle group, it’s not really working especially hard in the pedal stroke. Compare this to the powerhouses of glute maximus, the quadriceps and the calves, and those muscles at the back end of the pedal stroke probably aren’t contributing an enormous amount of power.

Should we all be training to engage more of our hamstrings though? Is this the secret to unlocking hidden power? Well, if you are a track rider or a road sprinter, then there is absolutely validity in this. However, for the vast majority of us are not sprinting for the line in a race or riding the team pursuit, we’re simply trying to become better weekend warriors.

We can spend several hours using a Wattbike to create a perfect circle with our pedal stroke, but when we start to fatigue, our body starts to prioritise metabolic efficiency over mechanical efficiency. What does this mean? Well, as an example, think about all of the individuals you see at the end of a marathon bent double, feet barely clearing the tarmac, swaying from side to side. This is far from an efficient way to run. In fact, it’s an absolute disaster, but what the body is trying to do is protect its metabolic processes (survival) over technique. The body is just trying to survive at this point by conserving as much energy as possible.

To see the most efficient running form, you only need to look at athlete running the 100M. Long stride length, strong arm drive, forefoot landing, high cadence. But how many marathon runners do you see holding this form throughout 26.2 miles? This is a similar story for cycling. Yes we can maximise the recruitment of the upstroke, but not for prolonged periods or time. As the body fatigues it will revert to focusing on the downstroke to simply get us home in one piece.

For some individuals however, there may be enough recruitment of the hamstrings and hip flexors to increase power output by a notable amount, even when riding easy. However, it’s important to acknowledge that this isn’t free energy. It still requires oxygen and energy to contract that muscle, so we’re still paying a cost to recruit those muscles on the upstroke. As above, very useful if you are looking for higher power output in a short timeframe, but it’s going to be hard to keep all those muscles firing over the course of 100 miles.

So yes, there will be increased muscle activation, but it won’t contribute nearly as much as some people would have you think.

This is probably the biggest benefit for me personally. When I’m clipped in, I know that I can accelerate hard out of a corner or up a hill without any fear of my feet flying off the pedal, and the aforementioned pedal slamming into my shin. While we may not be doing a huge amount of acceleration in triathlon, we still need to get up to speed coming out of corners and when passing competitors.

So as we’ve established, the upstroke probably doesn’t contribute much to the stroke mechanically, but using cleats will still help teach you a more efficient pedalling motion. Most people will have a very ‘stampy’ pedalling technique when they start riding, which cleats will help transform into a more efficient stroke, even in trainers. With cleats and an appropriate saddle height, it helps you push down through the whole of the downstroke, and backwards after you’ve finished pushing downwards. Imagine you’re scraping something off of the bottom of your shoe and this will help you recreate the correct motion.

Even when you’re not riding in cleats (I ride short distances in my trainers on top of clipless pedals all the time), you will carry that same pedalling motion over. You will obviously lack any form of upstroke, but from 12 O’clock to 7 O’clock you will be contributing something, where as before you may only have contributed power until around the 4-5 O’clock position.

If your cleats are setup correctly (I recommend everyone gets a bike fit), they lock your knees into what should be a safe position. This reduces the chance of your feet pointing out to the sides as you ride, which places extra strain through your knee. You should still have a degree of float in your cleats in almost every scenario in my opinion, but it should reduce your chances of picking up injuries.

Many of us will have memories of pedalling so fast that our feet come off of our pedals. Being locked into the pedal allows for a higher cadence without risk of this happening. Can you imagine a sprint to the line in a professional bike race with the risk of someone’s feet flying off the pedals?

A skilled rider can still pedal in trainers at a high cadence, but as with pedalling technique, it’s a technique best developed while clipped in, and then applied to your ride to the shops.

Ok, so by now we’ve got a pretty good idea of what cleats are and how they can benefit our cycling, but which cleats should we be using? The cleats you buy must match the pedals you are using. The main standards at Shimano SPD, Shimano SPD-SL, Look at Speedplay, but there are some lesser known brands out there as well. If you’re unsure which cleats will be compatible with your bike, ask your local bike shop who will be able to sell you the correct cleat.

However, if you’re buying pedals for the first time, which standard should you go for? Speedplay is the favourite of many bike fitters, but it’s definitely at a premium price point. Shimano SPD are generally used more by off road cyclists, as they are a recessed cleat, meaning you can walk around in them much easier. All other standards are much larger and clunkier. I know some cyclists who swear by the standard SPDs as they find them much easier to walk in, however I generally point cyclists in the direction of the larger, clunkier cleats. The reason is less to do with power transfer/comfort, and more to do with the shoes themselves. A good 80% of cycling shoes on the market use the three bolt design that larger cleats use, while only a handful accept the recessed SPD style. As the fit of a cycling shoe is paramount for cycling comfort, by opting for a recessed cleat you could be painting yourself into a corner.

It seems unfair of me to preach the benefits without looking at some of the downsides:

-They are not especially beginner friendly, as the unclipping motion is unnatural and leaves you likely to fall off the bike after failing to unclip.

-You will fall off your bike as a result of failing to unclip at least once. Probably more.

-The pedals are expensive, as are the shoes. Even if you were to look at the cheapest pedals and cheapest shoes, expect to walk away £100 lighter.

-Cycling shoes are not designed for walking in. You will be at a high risk of slipping over and falling in your cycling shoes. Each cycling club has a story of a hapless cyclist who fell face first down the cafe stairs because of their cleats.

I hope this article has given you some insight into the theory behind cycle cleats. Now get out there and ride hard.